26 September 2023

By Tim Koch

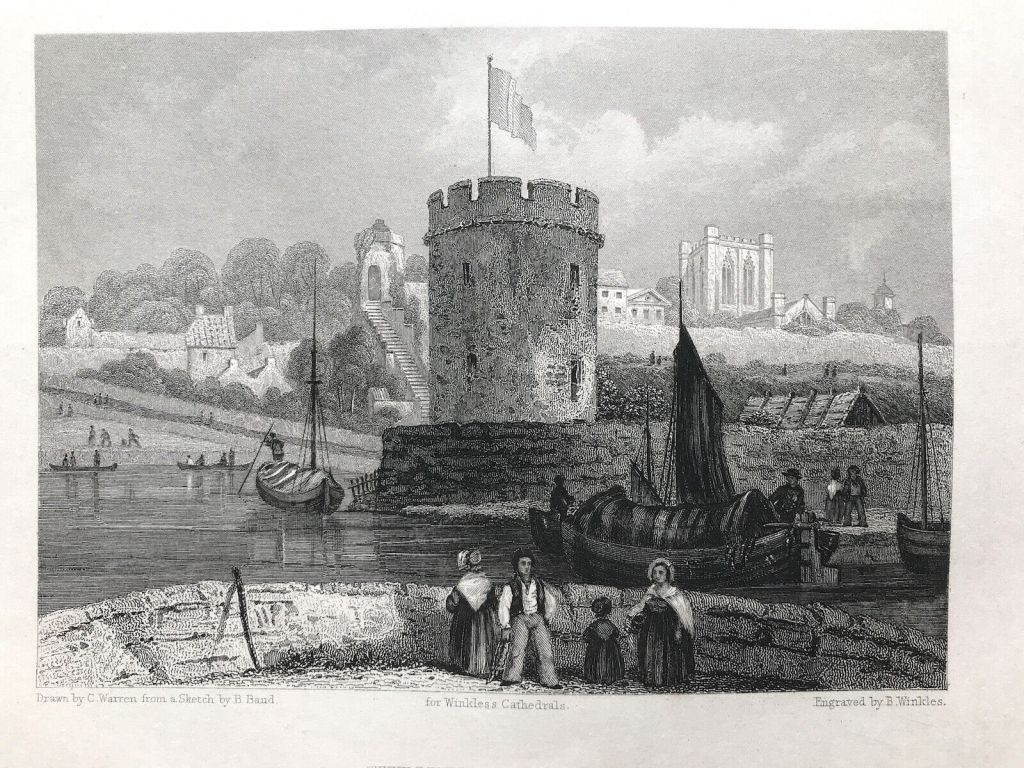

There are five River Dees in Britain, Tim Koch is still concerned with the one that goes through Chester. (Part I and II)

The Revival, 1829

After a ten-year hiatus, the seventh Chester Regatta, an event that had run uninterrupted from 1814 to 1819, was held on 19 July 1829 in honour of the anniversary of the Coronation of George IV who had been King for eight years by this point.

The Chester Chronicle of 24 July 1829 gave some hints on how this revival came about:

Members of the Chester Yacht Club and a few spirited individuals entered into a small subscription for the purpose of having a regatta on a small scale on our river, above the weir… in the hope that it may be only the commencement of better things in this way hereafter…

The mention of the “Chester Yacht Club” as the organising body for the rowing regatta is strange, the local newspapers referred to the Yacht Club a few times in 1829 and again in 1832 but that is all.

Intriguingly, the Chronicle article mentions an eight-oar belonging to the 67th (South Hampshire) Regiment of Foot. Previously, I had only known of London based regiments, particularly the Guards, involved in apparently serious rowing:

Among the company on the water were the Hon. Col. Molyneux and a chosen crew of his brother officers of the 67th Regiment in their fine eight-oared galley who… proved that they can handle the oar as effectively as the sword…

The veteran Captain Oldham was the Umpire… and the names of the victors were announced by the speaking trumpet…

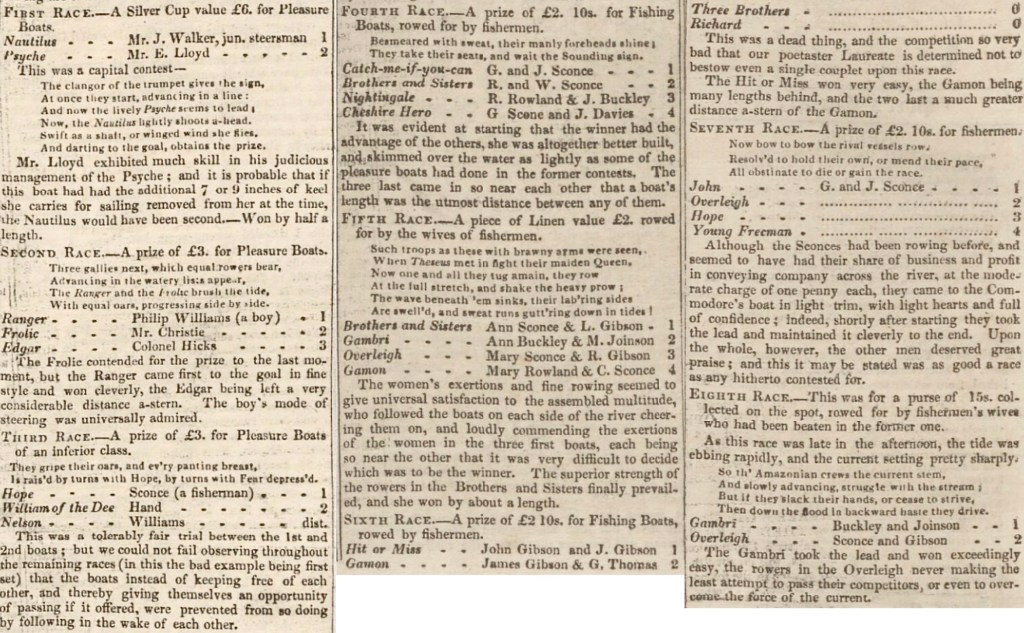

The 1829 regatta was double the size of the last one in 1819, it offered eight events with prize money totalling £22. There were three races for “pleasure boats”, two for fishing boats rowed by fishermen, one simply for fishermen and two for fishermen’s wives (the first time that women’s racing had been offered since the first Chester Regatta in 1814).

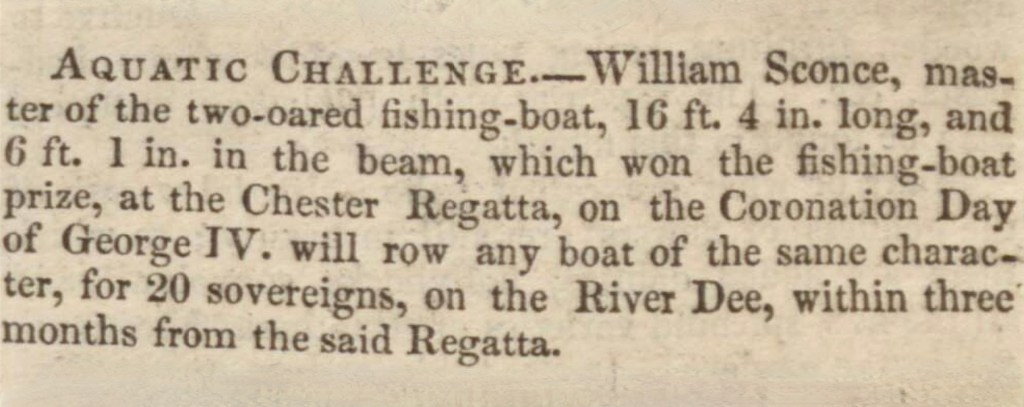

In the race for “Pleasure Boats of an inferior class”, it was noted that, Hope was rowed by “Sconce (a fisherman)”, generally however, whatever a “pleasure boat” was, a craft that was not a working boat was likely to be owned by someone of reasonable wealth and status. This was an indication of things soon to come.

Amateurs, 1830

No women’s races were offered at the 1830 Regatta but there were some firsts:

Of the four races put on, three were for “Amateurs”. This was the first time this word had been used in the Chester Regatta notices.

The first race for six-oared boats was held.

Two four-oared races for Amateurs were offered, one for “Gigs” and one for “Boats”. I am guessing that the latter were heavy boats and the former light, presumably an attempt to differentiate between working boats and those built for racing.

An entrance fee for each amateur boat (though not for the fishermen’s boats) was charged for the first time. This would have put the regatta on a better financial footing with less reliance on the generosity of local subscribers (those who gave money for prizes).

It was stated that, Any amateurs with two oared boats willing to make a match or run a sweepstakes, the same to be under the regulations of the Committee, by whom a prize will be added… The Committee, if desired, will assist in forming private matches or sweepstakes…

Gentlemen Amateurs, 1831

The next year, 1831, there were some changes:

The most significant aspect of the 1831 regatta was the inclusion of the term “Gentleman Amateur” for the first time. Unfortunately, we cannot be sure how the regatta committee defined a gentleman or an amateur, but we can be certain that the Chester definitions of 1831 were more lenient than those of the later “Putney Rules” of 1878* as Chester gentlemen could still row for prize money, gamble and be coached and steered by professional boatmen (though by 1834 the rules had stopped professionals steering gentlemen’s boats).

I speculate that the definition of a gentleman may have been an arbitrary one, depending on the whims of the regatta committee of the time. Sometimes perhaps, a gentleman was someone with a private income or at other times possibly a confident clerk could pass muster. As we shall see, there was an extreme variation in 1840 when a currier (a person who dressed and coloured leather after it was tanned) was allowed to race in a gentlemen’s boat.

A race for women in fishing boats was brought back in 1831 and no entrance fee was asked.

There was no mention of private matches or sweepstakes but, according to demand, events would be put on for boatmen and for fishermen. I assume that a “boatman” was someone who rowed as part of his trade but who was not a fisherman. On the day, Chester 1831 had four races for gentlemen amateurs, two for boatmen, one for fishermen’s wives and one for coracles.

A Poor Show, 1832

The Chester Regatta of 1832 was the tenth and was a strange affair suggesting a new and inexperienced committee. It seems that the organisation was left very late and, three weeks before the first proposed date, the Chester Courant of 5 June wrote that, Prizes of plate and money will be contended for and the matches will be fixed by the owners or crews of the boats, subject to the approbation of a committee of management. The implication seems to be that specific events would not be offered and the schedule would be demand led.

The Chester Chronicle did not report on the regatta at all and the Courant gave it just a few column inches claiming that racing started just as it was going to press. However, Glass and Patrick’s Royal Chester Rowing Club Centenary History (1939) quotes a poster from 1832 which offered races for “amateurs” and for “boatmen” each in six-oar and four-oar gigs. There was also a two-oared event for amateurs and a race for women in fishermen’s boats.

Two weeks later after the 1832 regatta, the Courant reported on some complaints.

In the race for Six Oared Gigs rowed by Amateurs, prize £10, three entries were made but two of them objected to the third as it was rowed by “picked men”. What was meant by this we can only speculate, were these men technically amateurs but ones who were cynically put together simply to win money? The “President of the Regatta Club” had previously stated that they would not be allowed to row, but on regatta day they were in fact permitted to race. Thus, their two opponents refused to compete, and the picked men took the £10 without a contest.

In the race for Four Oared Gigs rowed by Amateurs, prize £7, three boats raced but those that came second and third claimed that they had been fouled by the winner. The umpire said that he would report to the committee for their decision, but the first placed boat eventually got its £7 without any judgement having apparently been made.

A Fallow Year, 1833

Perhaps it is not surprising that no regatta seems to have taken place the following year, 1833. However, the Chester Courant of 3 September 1833 did report, We understand a regatta will take place upon the Dee… next year under the patronage of Lord Robert Grosvenor and J. Jarvis, (Parliamentary) representatives of this city who will give a cup to be rowed for on the occasion. The break of a year seems to have been used wisely and a very different regatta was organised by a mostly new committee in 1834.

Notable Changes, 1834

Both local newspapers were keen to state how competent and respectable the new organisers of Chester Regatta now were, emphasising the patronage of the local Member of Parliament, of Lord Grosvenor and of the High Sheriff of Cheshire. It stressed the approbation of the Mayor and noted the good character of the committee stewards which included an army major, a naval lieutenant and a doctor.

It was not only the organisers who were of high repute. After the regatta, the Chester Courant of 2 September reported:

This long-expected piece of amusement came off last week when it succeeded in drawing to the banks of the river a very large and splendid concourse of people, consisting of probably not less at one period of six to seven thousand individuals among whom many of the most respectable inhabitants of the city and neighbourhood, and a galley of female youth and beauty, such as no city of the same magnitude as Chester could surpass in the kingdom.

In fact, as it was a free day out, much of the city would have attended, including all social classes and all degrees of respectability, age and beauty.

As the above summary shows, the Chester Regatta of 1834 introduced the classifications of competitive rowing that would dominate the sport in Britain only much later in the century. It recognised Gentlemen Amateurs, Tradesmen Amateurs (“All amateurs not boatmen or fishermen”) and Professionals in the context of Chester (“Boatmen or fishermen”). Further, for all the men’s races, skiffs and gigs were the only boats referred to.

Thus, 1834 was a very significant year in the history of Chester Regatta. At this stage, the gentlemen who organised it were not trying to exclude working men and were content for all classes to compete in the same regatta – but just not in the same race.

Failure Follows Success, 1835 – 1837

After the apparent success of the 1835 Chester Regatta, it is surprising that there were no such events during 1835 to 1837. The Chester Courant of 21 June 1836wrote, It is with pleasure we announce that a subscription has been set on foot for the purpose of having a regatta on the River Dee in the course of the ensuing autumn. However, nothing seems to have come of this, presumably there were not enough subscribers (sponsors). Was this finally the end?

* There was more than one set of so-called Putney Rules. The Putney Rules of 1872 concerned the conduct of boat races but the most famous edict from the Embankment followed a meeting in 1878 between the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Clubs and the principal London clubs. For clubs and regattas affiliated to what became the Amateur Rowing Association, it decreed:

An amateur rower or sculler must be an officer of Her Majesty’s Army, Navy or Civil Service, a member of the Liberal professions, or of the Universities or Public Schools, or any established boat or rowing club not containing mechanics or professionals; and must not have competed in any competition for either a stake, or money, or entrance fee, or with or against a professional for any prize; nor have ever taught, or assisted in the pursuit of athletic exercises of any kind as a means of livelihood, nor have ever been employed in or about boats, or in manual labour; nor be a mechanic, artisan or labourer.

Part IV, which will be posted on Thursday, 28 September, will show how Chester Regatta secured a more certain future.

“It’s the same the whole world over, it’s the poor what get the blame, while the rich has all the pleasure, ain’t it all a bloody shame “!