9 April 2018

Tim Koch discovers that Heaven is located in Central Europe.

Occasionally, my searches for new aspects of rowing history will take me down a non-rowing (but still interesting) path. This happened recently while I was scanning eBay for rowing material. I came across the above early 20-century postcard showing a boat race on a large lake surrounded by mountains. It was not a good picture, lacking any detail, and I would not have given it much consideration but for a handwritten explanation on the back:

Eguatic (sic) SPORTS. GUNTEN. 1 Sept 1918. FINISH of the RACE. BRITISH INTERNED v THUN. B.I.s WIN EASILY, 3 1/2 L. FIRST AND SECOND PLACE.

It was easy enough to discover that Gunten is a small village in the canton of Bern, Switzerland, located on the northern shore of Lake Thun, and that Thun is a nearby medium-sized town. The unanswered question was, who were the ‘British Interned’ rowing in Switzerland in the last month of the First World War?

Switzerland maintained a state of armed neutrality during the First World War, but only with great difficulty. It shared borders and populations with both sides, Germany and Austria-Hungary from the Central Powers, and France and Italy from the Allies. The Swiss government was shocked when neutral Belgium was invaded by the Germans in 1914 and decided to use humanitarian action as a tool of foreign policy in an attempt to keep the country out of the war, showing everyone in the conflict that Swiss neutrality could be useful.

In 1914, both sides agreed that prisoners of war (PoWs) too seriously wounded or sick to be able to continue in military service could be repatriated through Switzerland. By November 1916, 8,700 French and 2,300 German PoWs had been sent home.

The next step was the internment and treatment in Switzerland of PoWs who, though sick or badly wounded, could still aid their country’s war effort if they were repatriated. A system was established whereby Swiss doctors visited PoW camps to select potential internees, the final decision being made by a board of two Swiss doctors, two doctors from the country holding him captive, and a representative of the prisoner’s own nation. There was no quota system, each case was decided on its own merits. Writing in 1914 – 1918 Online, Thomas Bürgisser of the University of Basel noted that Swiss humanitarian action also brought internal benefits:

While Swiss society during the war was divided along the language borders – French-speaking Switzerland generally was in favour of the Entente; whereas most people in the German-speaking part of the country supported the Central Powers – the internment of members of both warring parties was an opportunity to reconnect the quarrelling social factions in a common humanitarian cause – at least according to the picture drawn by the propaganda.

Between 1916 and 1918, 68,000 wounded prisoners of war were accepted for recovery in Switzerland. About half were French, one-third German and the remainder mostly British or Belgian – though soldiers from all over the British Empire were also interned. The Germans were sent to the German-speaking regions and the French and Belgians to the francophone areas. The British were in south-west Switzerland, east of Lake Geneva.

As the first internees arrived in Switzerland and travelled through the country, they were often surprised to be greeted by thousands of local people who had turned out to welcome them. Humanitarian action may have been a cynical policy by the Swiss government, but many of the Swiss people took it at face value. Britain’s ambassador to Switzerland wrote:

I have never before in my life seen such a welcome accorded to anyone… At Lausanne, some 10,000 people, at 5 am, were present at the station… Our men were simply astounded. Many of them were crying like children… As one private said to me: ‘God bless you, sir, it’s like dropping right into ‘eaven from ‘ell’.

The local people seemed particularly enthralled by the arrival of some of the more exotic foreigners. In 1918, a local newspaper complained, ‘…during the arrival of Indians, Senegalese negroes, brown and yellow Asians, the crowd is racing to distribute gifts… [but] our soldiers were left with nothing’.

Initially, it was planned to build barracks for these men to live in. However, the war had virtually destroyed Switzerland’s tourism industry as it had been reliant on British and German guests. The result was that the Alpine resorts competed to house the internees in their empty hotels, the former PoWs’ respective governments paying the bills (though, if their wounds or illness permitted, interned other ranks were also expected to work).

Thus, thousands of wounded soldiers were sent to resorts like Verbier, Zermatt, Davos and many other now well-known skiing destinations. Decent food, mountain air and peaceful surroundings aided many of them to return to health. Spirits were particularly lifted when the Swiss to allow parents, wives, and (suitably chaperoned) fiancées to visit.

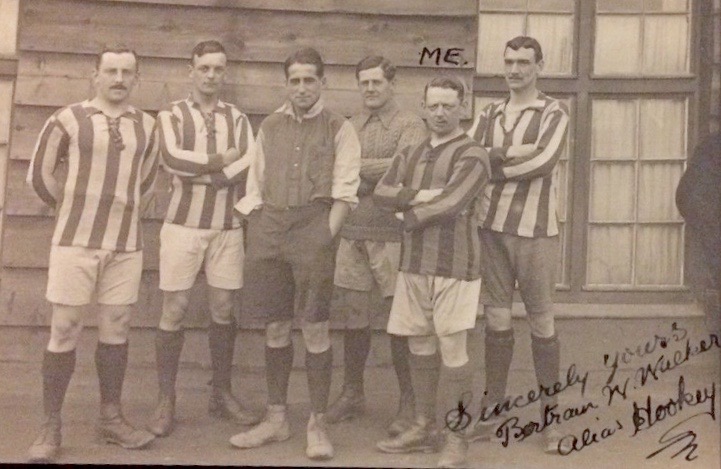

However, life for the internees was not necessarily easy, they were still under military discipline, enforced by the Swiss army. There were breaches of discipline, mainly caused by ‘alcohol and sexual immorality’. In response, access to alcohol became restricted and possible alternatives to fornication were encouraged – particularly sport.

In Dropped from ‘ell into ‘eaven: Interned PoWs in Switzerland, 1916-1918, Susan Barton wrote:

Sport played an important role in the life of internees. Football, between teams from different hotels, was a big thing. There were regular matches and a league competition. As the war progressed there were tournaments between internees in different villages and towns. Swiss teams joined in too… individual sports like tennis were important preoccupations.

At [the British camp in] Mürren, as well as skiing…. curling, skating and ice hockey, enjoyed particularly by Canadians, there was the Total Abstinence Rambling Club with seventy members, an orchestra and wood carving classes. There was also football, tennis and boxing. There were football, cricket and hockey leagues between the different hotels.

Switzerland’s ‘calculated humanity’ eventually paid off and its neighbours increasingly viewed its neutrality in a more positive light, something that lasted through the Second World War and which still continues to this day.

As to the internees, many of their accounts stress their boredom (the British camp at Mürren, for example, was virtually cut off by snow for seven months of the year) and their frustration at being prisoners. However, it is difficult to believe that fighting on the Western Front was preferable to sitting the war out in a Swiss Alpine holiday resort, particularly by those who had already ‘done their bit’ and had been wounded in the process. Thomas Bürgisser:

Despite [some] criticism, the internment of sick and wounded alien PoWs as a whole was hardly ever questioned by the [Swiss] public, the media or by political parties. The internees themselves were well aware of the privilege they enjoyed by being allowed to rest, cure their ills and regain new strength in Switzerland.

Endnotes:

The Times newspaper of 4 November 1916 listed 96035 Gunner AF Lee as wounded.

‘Seeclub Thun’, is a rowing club founded in Thun in 1910 and which still exists today. It seems likely this was the club that the British Internees rowed against. It is (and presumably was) German-speaking, and this would have made the race an even more fiercely competitive event.

A book published in 1919, The British Interned in Switzerland, by HP Pocot, the British Military Attaché in Switzerland during the Great War, is available to read online.